Researching Historical Children’s Wear

In the past years, I researched historical clothing a lot, and I plan to do even more so in the years to come. But in my research, the focus is almost always on women’s fashion. (And more specifically on the women’s wear of the upper classes) To a lesser extent, I’ve focused my attention on men’s clothing. I haven’t actually made a man’s costume yet, but at least on the subject of men’s wear, there is still sufficient information in the history books. But a subject that is almost never covered in historic costume books, at the most as a footnote at the end of a chapter, is children’s wear.

To some extent, it is understandable that children’s clothing is not well researched. Because for a long time, children were treated and therefore dressed as miniature adults. So when we are talking about the clothing of the middle ages or the baroque, the information that you read about adult’s clothing is also applicable to children’s wear

But during the 18th century the philosophy about children in general changed from the idea that humans were born in sin, to the idea of natural innocence in children. The French philosopher Rousseau was a big influence in this point. His idea of the natural child was one that wears comfortable clothing, and is not encumbered in rigid stays. From about 1750 or 1760, we see a change in children’s wear. All children up to age 6 wore frocks. In fact, up until about the 1930’s or 1940’s, all baby’s and toddlers were dressed alike, in dresses. Without differentiating between boys and girls. After that, boys wore long pants, and girls wore simple straight dresses, often made of muslin. Under these dresses pantalettes (long pants-like undergarments that covered the legs) were worn. After age 12, children were deemed ready to wear adult style clothes.

Around 1800, after the French revolution, we see that adults adopt this fashion, that has been children’s wear for about forty years, too. Men started to wear long pants instead of breaches, and women wore long slim often white dresses. So during this period, children basically looked like miniature adults again.

But when the romantic period came around, and women’s fashion started to change, with wider skirts and sleeves, so did children’s wear. Children basically looked like adults again, only with shorter dresses, shorter sleeves, and a pair of pantalettes sticking out from under their skirts. When the crinoline came around during the 1850’s, children’s fashion changed with it to follow adult fashion on the outside, but they did not adorn the same undergarments. The skirts children wore grew wider, but they did not wear a crinoline to support them. The same is true for the bustle era. Children’s dresses now came with more fullness at the back, but they didn’t wear bustle cages either. They relied on folds of fabric or bows to mimic the adult silhouette.

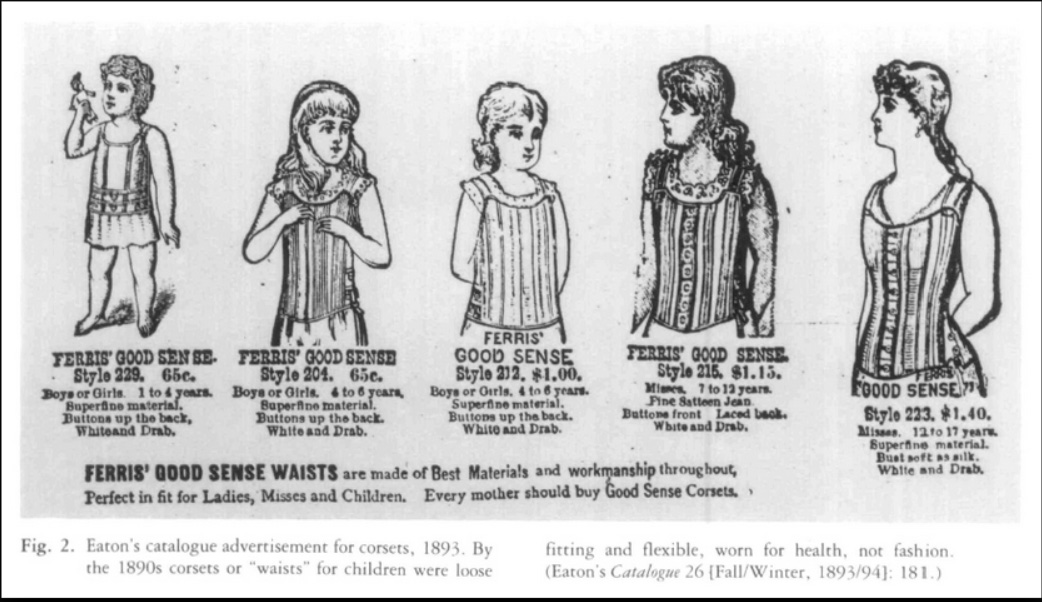

However, while children did not wear steel cages to give their skirts a fashionable shape, they still wore some form of the corset. While a lot of people may gasp in horror when they hear that, it is not as bad as it may seem. When we think of a corset, we mostly think of a tight, waist defining, steel construction. But as you can see in the add above, children’s corsets took on a different shape. The corset (also called a waist sometimes) was lighter and more flexible than their adult counterparts. They are also much straighter, and do not define the waist in any way on the younger children. The corsets for children up until age 7 are described in adds as being soft and having buttons down the back. So lacing the corset tight was not even possible. Only the corset on the far right shows some kind of waist definition, but that corset is only for children age 12 to 17. In other words, adolescents who are developing female forms. So the corset does not shape the body, but follows it’s natural forms.

The corsets for children were not worn for fashion reasons, but for health. The Victorians believed that a corset of some sort was necessary for the health of a person. It kept the body warm and kept the posture straight. Two very important pillars of health for the Victorians. The corsets were more an extra layer of clothing than a typical Victorian style corset. So when you first hear Rousseau state that children should not wear stays with steal boning, and than hear about children’s corsets, this is not a contradiction. They simply modified their normal undergarment, which they considered essential for health, so it would fit better in a child’s active lifestyle.

This is mostly how far we come when we research children’s wear in books. They just simply answer the question: does it resemble adult wear or not? So where are we to turn to do research on historical children’s wear if literary sources are insufficient? Well, fortunately we have a few other sources besides books. The first one is the most obvious: clothing items in museums. Museums that have quite a substantial textiles collection often have a few children’s outfits too. Unfortunately, they are not on display a lot. But luckily, more and more museums have an easy to search digital archive, with clear photographs of the items. The photographic evidence and the descriptions can be a good aid in research.

But unfortunately, only the most special and well preserved items are displayed in museums. If we want to know more about day to day wear, we have to look at another source. But one of the most useful sources for researching children’s wear is one some of us might find quite morbid. That is the Victorian practice of post-mortem photography.

Taking pictures of deceased children, sometimes even posing them with living siblings, might seem weird, morbid or even wrong to some people today. But as with most subjects of historical research, it is important to look at it from a contemporary perspective. Imagine you are a Victorian woman, with quite a few children. You work hard, but money is still tight. So you haven’t taken your children’s to get their picture taken, ever. You have no pictures, no paintings, nothing with you children’s face on it. And then one of your children dies. You are about to bury them, and you will never see their face again. It is very natural to want something to remember them by. So you can their face when you miss them so much. I can imagine that you would scrape the funds together, and pay a photographer to make your baby look as lifelike as possible.

(edit: I now have found an article stating that a lot of photographs that are said to be post-mortem are in fact not. The stands visible in the photographs seem to also have been used on living people to keep them steady during long exposure time. Read more here)

Also, the Victorians had much more contact with the dead than we have today anyway. They did not have the funeral industry as we know it today. Yes you had undertakers, but they were mostly involved in the process of actually burying them, and not so much with caring for the deceased person. People died in their homes more often, instead of in hospitals like these days. And the process of washing and caring for the body, holding the wake and prepping them for the funeral was all in the hands of the family. So there was less fear of the death in the society

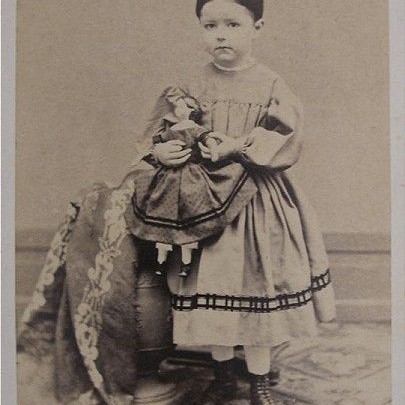

The interesting thing about studying these photographs is that you get a chance to see dresses that may not have been considered important enough to end up in museums. We can actually see the children’s dresses on a person. In these photographs we can see that, while the general silhouette mimicked that of an adult garment, these clothes fit the children much looser than adult wear. Also, they have far less decoration than adult dresses. This shows that while people tried to mimic the adult fashion in children’s wear, the idea that children should have more room for movement, like Rousseau stated a century before, still had some merit. Or maybe it was simply because children grow, and mothers wanted them to wear their clothes as long as possible. Whichever it was, the clothes do seem a little more roomy than their adult counterparts.

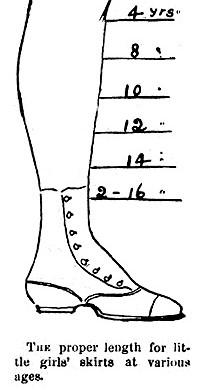

A downside of studying old photographs is that you can’t see the colour of these garments. But for that we have another great research subject: fashion plates. I find the fashion plates which feature both adults and children the most interesting, because in those cases you can compare where the children’s wear deviated from adult fashion. Most obvious distinguishing factor is the length. While adult women wore skirts to the ankles or the floor, children’s dresses were shorter. How short depended on the age of the girl. This drawing shows where the dress should end based on the age of the child.

Besides the length of the dress, another factor differentiating children’s from adult dress was the fact that children were not permitted to wear formal wear. A child’s best outfit was always their Sunday best, beautiful and neat, but for day wear. With long sleeves and a high neck. You would never see a child in a ballgown with a low cut bodice. Children were only permitted to wear these when they turned the age of around 16, when they also started to wear full length dresses and other adult fashion. Until this time young girls also wore their hair down, mostly in ringlets or braids, while adult women always wore their hair in an updo

All in all, I think we can state that children’s fashion generally followed the lines of adult garments. However, from about 1750 people started to realize that children needed more freedom of movement. So they started to modify children’s clothes generally follow the adult fashions, but modifying it to give a more relaxed fit, with shorter skirts and a looser fit. This way the children would not be hindered in their movements doing all the things that kids do growing up.

These are the factors I will keep in mind when making my own historical children’s dress. I’m working on a reproduction of a 1865 dress for an eight year old girl. But I will go into that in more detail in a coming blog post. If you have ever made a historical garment for a child, please tell me about it in the comments below. I am very interested to hear about what you made, for who and from which time period.